In conversation with Clare Bell and Brenda Dermody

Visual CommunicationPublished May 28 2018

A voyage of discovery

Every year, third and fourth Visual Communication students stage an exhibition of poetry as part of the Imram Irish language literature festival. Here we talk to the festival director Liam Carson, and poet Gabriel Rosenstock about this annual celebration of the Irish language, and their work as writers.

Liam Carson

Q. What prompted you to establish the IMRAM Irish Language Literature Festival, and how would you like to see it develop?

I founded IMRAM in 2004 following my own re-awakened interest in Irish, but particularly literature in Irish. I’d been brought up speaking Irish, and although my father had many classic works such as Seosamh Mac Grianna’s Mo Bhealach Féin and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin’s Fiche Bliain ag Fás, as a teenager I was under the thrall of the Beats and science fiction writers such as J G Ballard and Ursula le Guin. By my twenties,’ I’d drifted away from the language. Years later, though, I reconnected to Irish through the medium of its literature. First of all, there was Belfast poet Gearóid Mac Lochlainn, whose work is deeply embedded in the Irish language tradition, but also influenced by Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, reggae, punk and hip-hop music. MacLochlainn writes about my home—west Belfast—and learnt much of his Irish from my father. I recognised the city I grew up in his poems. Here was 1970’s and 1980’s Belfast—the soldiers, the helicopters, the sirens, the half-bricks, the plastic bullets and the Molotov cocktails. Here were people listening to Linton Kwesi Johnson and swimming between Irish and English. I then went on to read wonderful fiction by writers such as Micheál Ó Conghaile, Alan Titley and Daithí Ó Muirí, all of whom deal in the magical, the fantastic, using surrealism to probe the strange nature of our world.

The more I read literature in Irish, the more I wanted to hear and see the writers reading their work. And I couldn’t help noticing that Irish language writers were at the margins of Irish life. I'd had considerable experience working as a literary publicist and event programmer, so I’d decided to put that experience to use in promoting Irish language writing. It is not enough for a literature to exist. A literature needs readers. Writers need readers, listeners, they need a platform on which to sing their songs. In 2004, with the assistance of Poetry Ireland, I set out to create the IMRAM Irish Language Literature Festival. It was co-founder poet Gabriel Rosenstock who named the festival IMRAM—a ‘voyage of discovery’. It means constantly finding new ways in which to frame Irish language literature - through eclectic and imaginative event programming that fuses poetry, prose and music. IMRAM’s core mission is to bring writers and readers—and particularly new readers—together.

IMRAM’s message is positive—and places the Irish language and its literature at the heart of public life within a modern, energetic and multicultural framework. We believe that it is crucial to place Irish language literature in an international context. Irish language writers do not exist in some strange Gaelic ghetto cut off from the rest of the world. It is impossible to imagine Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill’s poetry without the influence of John Berryman or of Marina Tsvetaeva.

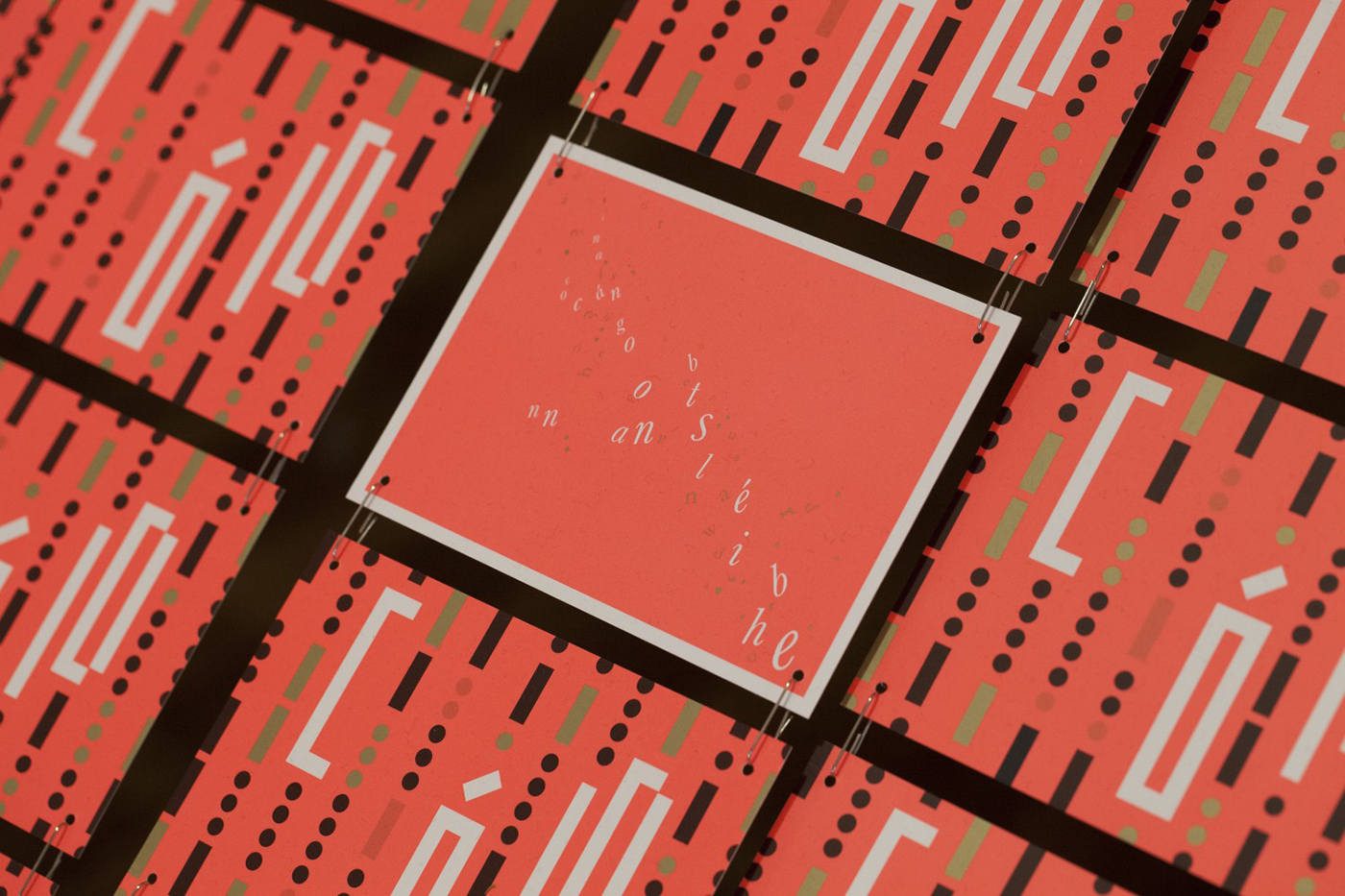

Q. What do the students bring to the IMRAM Festival with the Cló Draíochta Project and how does their work contribute to a reading of the poetry?

For a number of years now, IMRAM has been working in close association with the visual communication students, creating the annual Cló Draíochta Project. Poems and short prose texts are selected and given to students, who create imaginative new typographic interpretations of the poems and stories. In 2012, we took the project to the streets of Dublin, producing 30 large billboard poems. This meant that Irish language poetry had a significant visible presence, seen by thousands on their way to work. We have since worked on creating poem postcards, which again work on the principle of giving poetry a physical presence, and awakening the public to its existence. It’s important for IMRAM to engage with students, and to show them what exists in Irish language literature. I’d hope that the project might encourage everyone to further investigate the possibilities of the Irish language and its literature.

Q. What are you focusing on at the moment in your own writing?

My first book, call mother a lonely field, was a memoir exploring Belfast in the 1970s, the Irish language, punk music and comics, and was in large part about my parents. I’m currently writing a second memoir, tentatively called I shall walk into the night and fear no evil touch in the city of light. Its themes are city life, emigration, friendship, ageing and loss. The book will evoke pre-Celtic Tiger Dublin, the squatting subculture of 1980s London, and the Northern Troubles. It will include encounters with writers such as Padraic Fiacc and singers such as Shane McGowan and Johnny Brown of The Band of Holy Joy—and show how urban environments, popular culture and the wider zeitgeist shape an individual. It will deal with the elusive nature of memory and the shifting nature of personal identity. I do not write in a linear manner, but rather in a montage fashion, assembling a collage from disparate paragraphs, with narratives cross-referencing and illuminating each other. I’m also writing a children’s novel, Luna Benidorm and the Golden Salamander, at the specific behest of my daughter, Eithne. It includes mermaids, teenage spies, time travel and alternative dimensions or time-lines. It's one hell of a challenge, and the one thing a children’s novel needs more than anything is a fast-paced gripping yarn.