The AIDS Crisis in New York

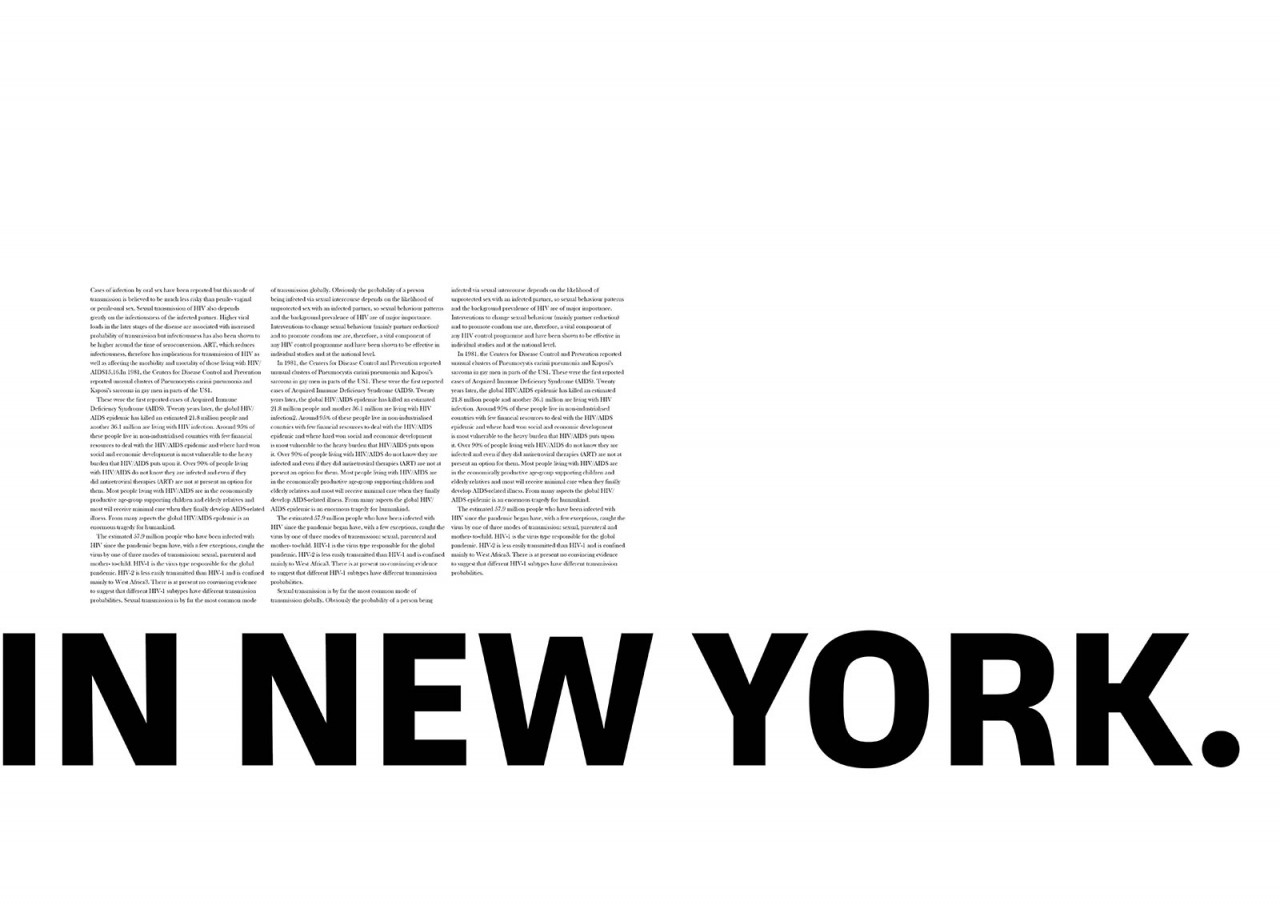

The topic of the AIDs epidemic was not one that I took lightly. A whole generation of a marginalized group was lost to the disease. Numbers are often not as impactful as they should be. The human mind cannot understand the impact of 1 million. I wanted to create a sense of impact emotionally, one that would bring us closer to the faces behind the numbers, to visualize the scale of the impact of the disease. 35 million have died globally since 1981 and 36.7 million people worldwide are living with HIV today.

I started with what we know, and what we are comfortable with. Heavily clinical information and no imagery. However, I didn't want to lose the opportunity to create some expressive design here. The columns give an implication of the high rise buildings of New York. I wanted to create intrigue with the starkness of the negative space and the heaviness of the headline, to mirror the stark reality of the negative space created by the epidemic. I pulled the headline across two spreads to emphasise the scale and ongoing nature of AIDS globally, even today.

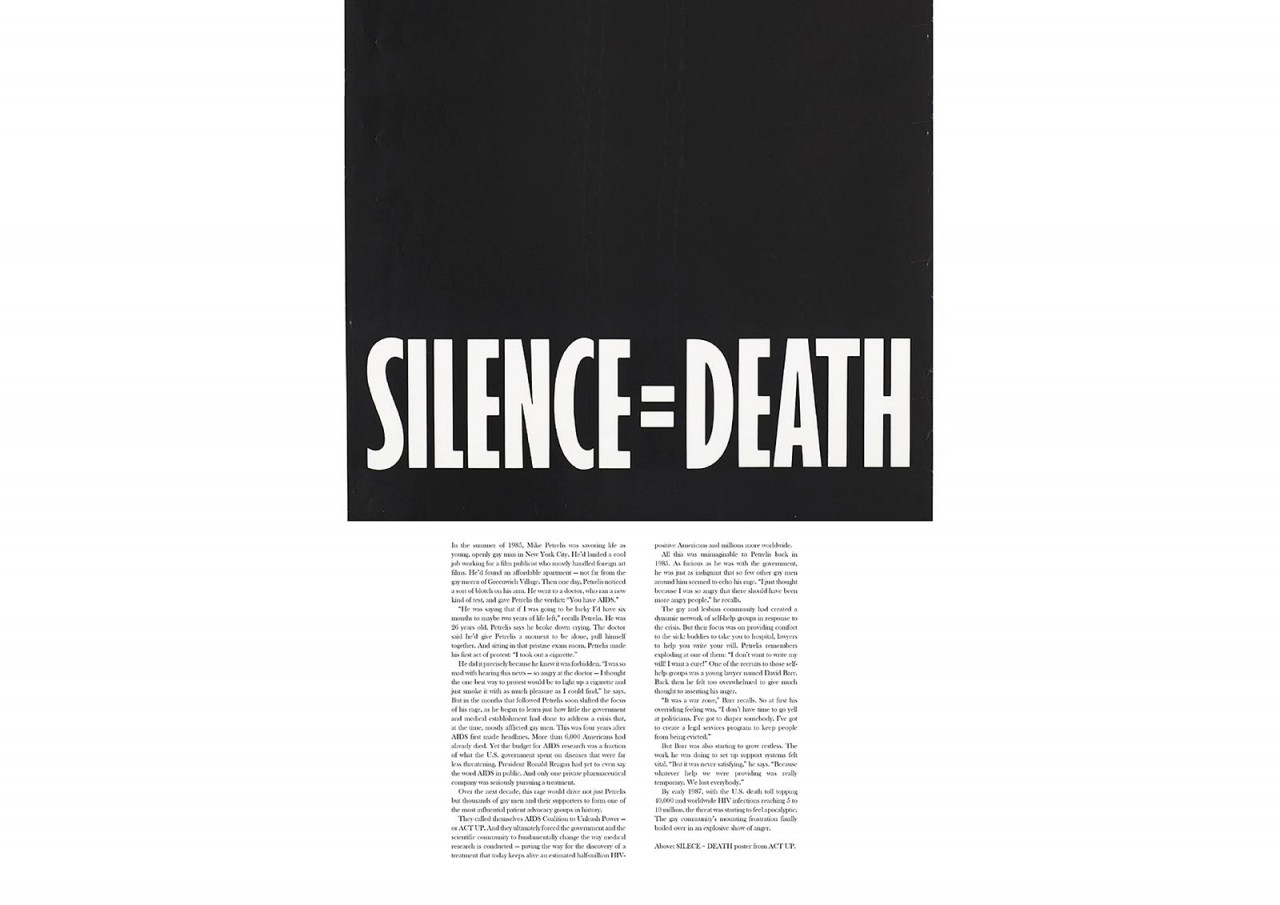

From there I started to show some more human aspects of the epidemic - a protest poster, a testimonial from a founder of ACT UP, an acronym for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. The organization was founded in the United States in 1987 to bring attention to the AIDS epidemic. It was the first group officially created to do so.

The spreads showing the rows of faces came from a New York Times memorial archiving those who died of the disease at this time in history. They are the real people behind the 120,453 total deaths in the city by 1990.

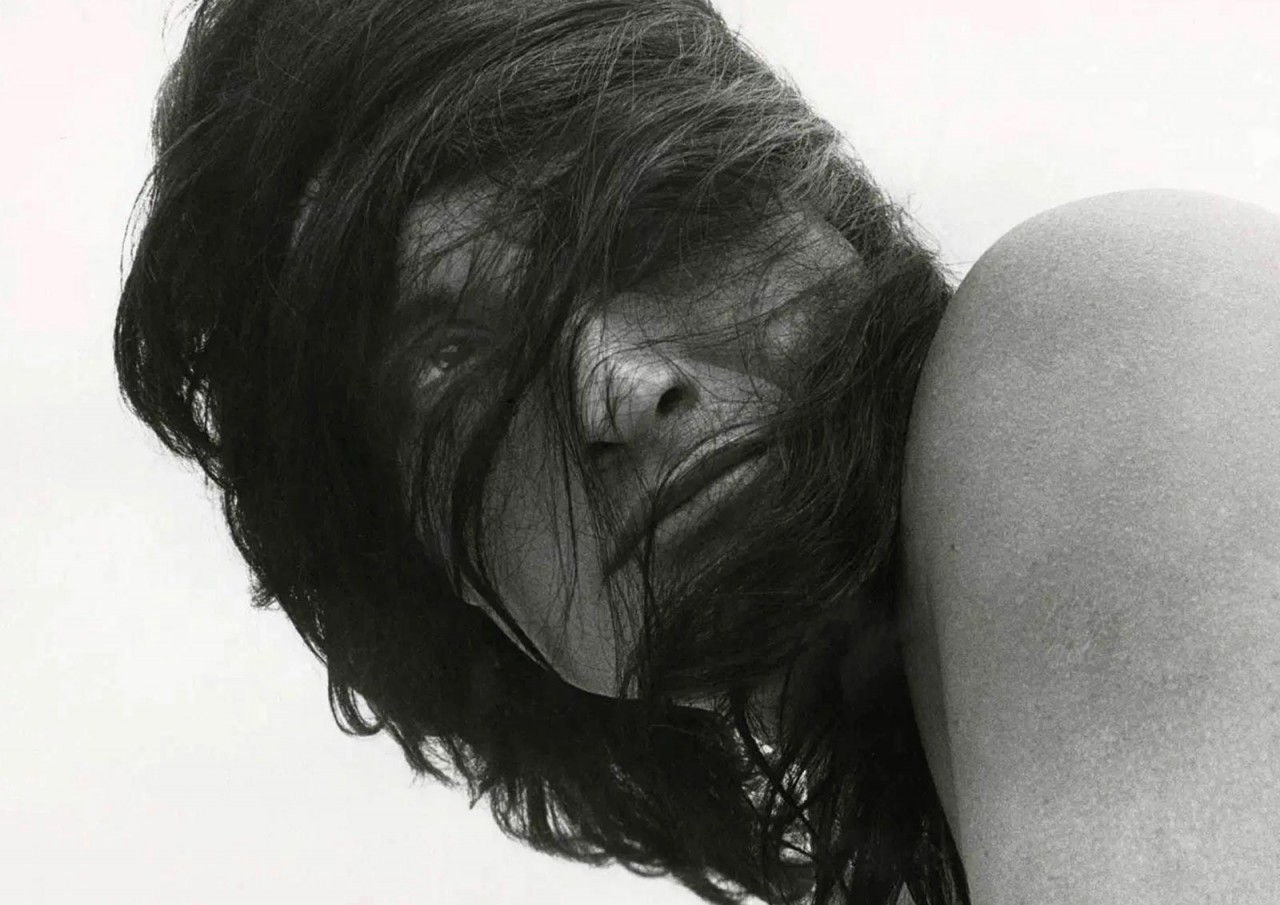

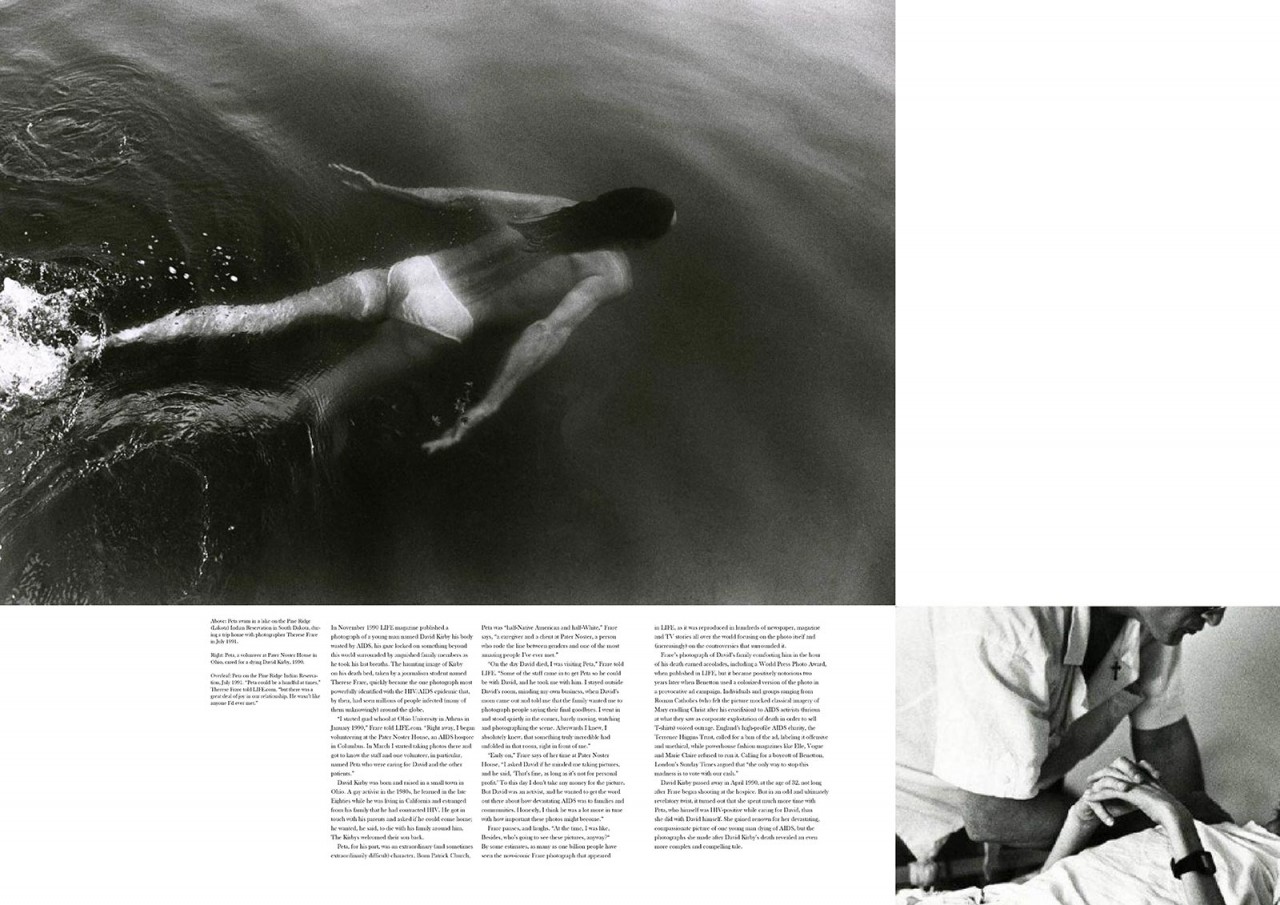

The final story follows the account of a photographer, Therese Frare, who volunteered at the hospital and was allowed permission to photograph the patients with their consent. She would go on to capture "the image that changed the face of AIDS", but this was not what interested me. One of her friends and colleagues, Peita, who had nursed the man in that famous photograph, contracted AIDs and eventually passed away. I wanted to show Peita as her friend, one that she loved and knew. Someone that only she could capture so intimately. I wanted to show the person that was lost rather than the patient who was sick and passed away.